About Elif Su

For 34 years

9 months

Hello,

I’m Elif Su Yılmaz.

Since I left you early—or, to put it

another way, joined the ancestors first, the task of telling my story has fallen

to my friends, colleagues, mentors, relatives, and my mother.

I don’t think they’ll exaggerate

when they speak of me, but still, it’s important to make sure they remain

rational.

I wish them the best of luck.

HERE I AM, THROUGH MY MOTHER’S PEN

(BUT WRITTEN AS IF SPOKEN BY ME)

According to legend—which, in fact,

has been proven true—I was an embryo in the first month of 1990.

When my mother found out she was

pregnant, she was terrified. As a young woman who had suffered from a serious

kidney disease in childhood, she knew the pregnancy would be risky. She

immediately consulted Prof. Dr. Emel Akoğlu at Marmara University.

During the kidney ultrasound, my

mother kept insisting, “Don’t let me see the baby. What if I can’t keep it

alive, what if I can’t give birth?” But when the radiologist saw that her

kidneys were healthy, she turned the ultrasound probe toward me, disrupting my

peace, and let my mother hear my heartbeat.

Upon hearing it for the first time, she

exclaimed, “Even if I die, even if I need dialysis, this baby must be born—this

baby will be born!”

Professor Emel replied, “If you want

it this much, even if you need dialysis, we’ll do everything for your kidneys

and the baby. You’ll give birth.”

(Thirty-five years later, at my

funeral, Dr. Emel Akoğlu was there, and my mother once again expressed her

gratitude: “Thanks to you, she was born. Elif Su was a gift.”)

In the end, I was born as a healthy

baby. I remember my mother taking me to thank Professor Emel, and in our

culture, that meant kissing her hand.

I was born on September 17, 1990, in

Istanbul. My father was a retired military officer due to disability and, at

the time, a trainee lawyer. My mother was a paediatric resident.

They were people living on a modest budget.

Childhood was always Istanbul—always

the Bosphorus, children’s activities, birthday parties at Koşuyolu Cafem, peace

festivals, my grandmother, grandfather, uncle, and cousins, Cenk, Nazlı, and

Sinem. Once, my mother and Aunt Sabahat took Alican and me to a children’s

opera at the Atatürk Cultural Center (before it was demolished). We were so

little, and we both fell sound asleep. Later, we laughed about how we snoozed

through the whole performance.

When I started preschool, I had no

idea my entire life would be spent as a student. And indeed, I left this world

shortly after completing my doctorate. So, my whole life was about

learning—learning how to learn and how to teach, creating materials to be

learned and taught.

When I started primary school, my

teacher, dear Emiş Gürbüz, called my mother in and said,

“Elif Su doesn’t walk down the

corridor during recess—she does cartwheels. I’m very worried she’ll hurt

herself.” That was probably the first official feedback that I was one of those

children who couldn’t be contained, for whom the world felt too small.

But I was a gymnast, and my desire

to dive into life with speed and risk was noticed early on.

From photos, stories, and my own

memories, I’ve gathered that I started sports at a very young age: first

gymnastics, then swimming, sailing, synchronized swimming, skiing, volleyball,

and later aikido and parachuting.

My life was always filled with

sports—long and demanding training sessions, competitions, medals. I always

loved sports—skiing, swimming, parachuting. I truly believed it was wonderful

for girls to be encouraged to do sport, to discover it, to live through it. And

if you’re worried that I got too tall, too muscular, or my shoulders

broadened—don’t be. These are all beautiful gains. For me, sport means

discipline, working together in solidarity, and learning through full

engagement of body and senses.

Books, games, toys, and playing

together within our apartment complex were also nourishing. I had lots of books

and many toys, though they weren’t all given to me at once. In fact, I later

learned that my mother used to go to a place called Tahtakale to buy toys

wholesale at affordable prices. She entrusted them to our dear neighbors,

Mehmet and Şükran Gümüş, and they gave me one toy each week as if it were newly

bought.

Whether resources were limited or

abundant, they had to be used wisely.

They say I was content and not

greedy. If I truly was, there were many factors that shaped me that way, and

I’m grateful for all of them.

I first learned that illness was a

part of life when I was diagnosed with asthma at the age of two and a half and

met the aerochamber device and asthma medications. Of course, having a mother

who was a medical doctor meant that my life was surrounded by sick children,

illnesses, doctors, and the constant effort to live and help others live as

healthily as possible.

In my twenties, I was diagnosed with

thyroid cancer and bipolar disorder—accepting them and continuing life as

beautifully as I could, in the face of these medical conditions wasn’t easy,

but I did it.

Meanwhile, the 1999 earthquake

struck. Twenty thousand people died in my country, Türkiye.

In response, many children across

the country packed their clothes and toys with their own hands and sent them to

children in the disaster zone. I joined this effort too.

Solidarity and collective action are

vital parts of life—not only in natural disasters, but also in personal

traumas, creative endeavours, and moments of joy. I learned the importance of

support and togetherness by living it.

Some say adolescence is a natural

disaster—I’m not sure. But I do remember the disaster-like parts of my own

adolescence vividly. At the beginning of that phase, when both my body and soul

were changing rapidly, I lost my uncle and then my grandfather. I grew up with

my mother and my grandmother, a fountain of love.

I had to stand tall, always move

forward, and life was hard. Changes I hadn’t chosen were happening. I was too

young to decide what I wanted to do in life. But aren’t we all a little too

young for trauma and big decisions, no matter our age?

When I was fifteen, during a trip to

Italy with my mother, we were at a restaurant in Florence where a gentleman was

hosting a music program. He passed the microphone around, inviting everyone to

sing, and handed it to me too. Though I had no musical training beyond piano

lessons—which I never liked—I began singing with blind courage. They invited me

to the stage, and I started singing song after song in front of people from

different countries. I received a lot of applause.

During the break, the host came over

to speak with my mother. “She’s a mezzo-soprano, you know? Is she receiving

training?” he asked. My mother, surprised, replied, “I had no idea.”

I was just a fifteen-year-old girl. It turned out that this gentleman was the

director of a conservatory in Italy. He said, “She must receive training.

Please bring her to us when she turns eighteen.”

That’s how we discovered my hidden

talent—singing, music.

Though I had been an excellent

student in primary school, I now found regular classes boring, even

suffocating. Singing lessons became far more appealing. My high school years

were filled with violin lessons, conservatory prep, vocal training, and bold

explorations of life.

Outside of the IB English program,

the other subjects didn’t interest me—they wouldn’t serve me at the

conservatory. I was good enough to pass the classes.

I graduated from Koç High School and

began preparing for conservatory entrance exams. But my mother—a wild and

witchy woman—insisted I also take the university entrance exam. I was adamant:

I would not prepare for it.

Still, my mother kept pushing books

and materials related to the exam in front of me.

I resisted studying. I didn’t

prepare, but I took the exam because of her insistence.

Despite myself, I won a scholarship

to study Art History and Archaeology at Koç University.

Now it was decision time:

conservatory or university? I thought long and hard, spoke with my vocal coach,

and eventually enrolled at Koç University.

That’s how the second chapter of my journey began.

Of course, my grades at Koç University

were excellent. I completed double majors and a minor, graduating with degrees

in Psychology, Art History–Archaeology, and Philosophy.

Let’s not downplay it—Koç is a tough

university to get into in Türkiye, and doing a double major and minor is no

small feat.

I took a lot of courses—both

academic and life lessons—but I still hadn’t found my path.

In my final year, while my mother

was attending the American Epilepsy Congress, she called me excitedly from the

U.S. She said I could work at a top center in pediatric

epileptology—neuroscience—and asked me to send my CV. I immediately replied,

“I’m not interested in neuroscience.”

I didn’t want to work in a narrow

field, like Nazım Hikmet’s image of “a white coat in a laboratory.” Instead, I

wanted to contribute to the world through transdisciplinary work and realize

myself. Disciplinary work wasn’t enough. Multidisciplinary work wasn’t enough

either. However, I still didn’t have an answer to the question, “What will I do

in this world?”

Like water (In Turkish, ‘Su’ means

water), like Elif (In Turkish, Elif accepted as upright or upstanding, as well as " alpha"), I was flowing straight ahead-but

I hadn’t yet found my course.

At first, I considered continuing in

psychology. I joined programs at the Institute of Behavioral Sciences and

explored what I could do in the world as a psychologist. I even registered with

the Turkish Psychological Association. But I realized that in a world so deeply

shaped by childhood trauma, I couldn’t pursue a path as a clinical psychologist

without constantly confronting the trauma of others, and I wasn’t sure that I

was prepared for that.

So, if I wasn’t going to be a

clinician, I thought I’d enter a field where I could blend psychology with

other disciplines. I began a master’s program in Psychology of Religion at

King’s College London. However, within a few months, I realized it wasn’t the

right fit for me—the approach was too categorical—so I decided not to continue.

Since I was already in Britain, I

thought I’d explore other universities and surroundings before making a

decision. Near New Year’s, in a riverside motel in Scotland, I looked out at

the water and decided that I wanted to pursue academic work with a contemporary

lens—combining psychology, art history, and philosophy.

I realized that my true field was

one where I could work transdisciplinarily: art and science.

I called my mother to share my

intention, my purpose, and my decision. She simply said, “Go wherever you’ll be

happy, and may you go safely.”

I applied to Edinburgh University,

Sussex University, Adelheit University, and Australian National University

(ANU)—and was accepted to all. My parents were thrilled, thinking I’d choose

Edinburgh, which was just a three-hour flight away.

But I felt ANU offered a broader and

more contemporary academic environment, so I chose it.

It was time again for reunion and

farewell.

I returned to Türkiye and departed

for Australia from Atatürk Airport with a backpack and a suitcase. My parents

were bittersweet as they said goodbye—disappointed that I had chosen somewhere

so far away instead of Edinburgh.

In Australia, I settled into a dorm

room at Burgmann College and began my Advanced Master’s in Curatorship and Art

History at ANU. I was surrounded by a massive library and an atmosphere rich in

science, art, and social justice.

From our perspective, Australia is

the edge of the world—but for students from Asia and Oceania, it’s close. Compared

to Europe, Australia felt like capturing the world’s image through a wider lens

and broader frame.

Almost all my grades were High

Degree. Life was going well—new continent, great education—it suited me.

With my supervisor Chaitania

Sabrani, I completed my thesis titled ‘Reclamations

of Power and Space Through the Abject: Franko B and Rashid Rana’, and

earned my master’s degree. I worked as a curator with Raquel Ormella in a 2018

exhibition, joined a Quidditch team, and explored different cultures and

traditions with friends from Asia and Oceania.

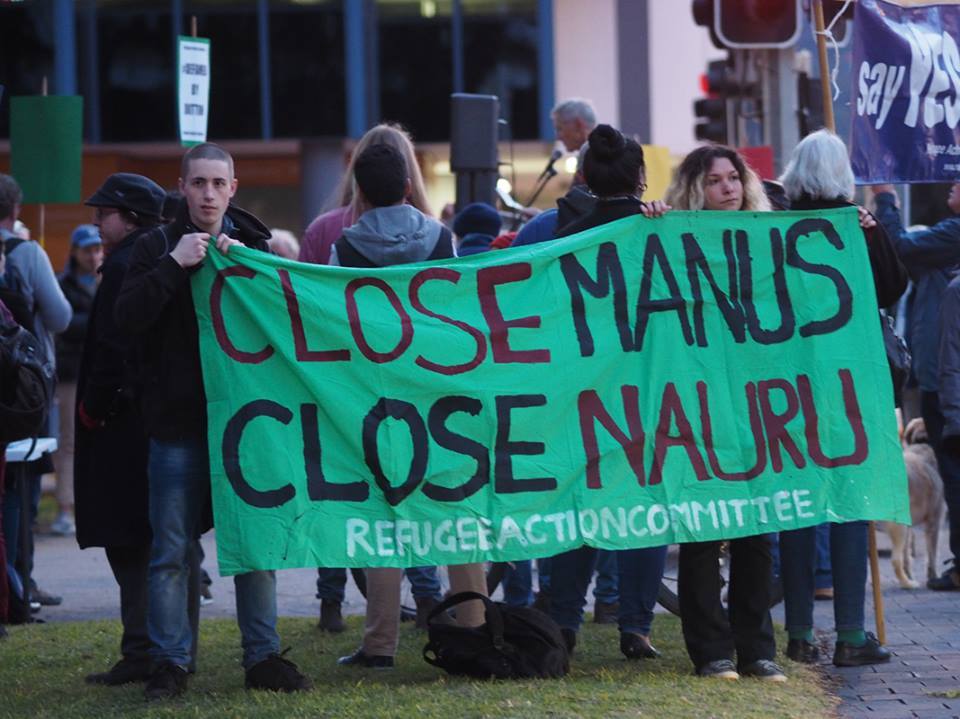

There was also the freedom to

protest against injustice—against racism, xenophobia, Islamophobia, and for

human rights. We could express ourselves and return home safely.

A few years earlier, a young person

trying to protect trees had a plastic bullet graze their hair—freedom of

expression mattered deeply.

Not just through protests, but since

childhood, I believed that the voice trapped inside me—against injustice and

domination—could be heard through science and academia.

Then the COVID-19 pandemic began. Like

everyone else, I was confined to where I was.

During the pandemic, the world

paused. Everyone paused. Perhaps we all felt trapped, wronged, and threatened

by death.

What did it teach us, that so many

people experienced similar struggles at the same time?

In a world where women, children,

the sick, the poor, and non-human animals are constantly subjected to injustice

and discrimination, it seems that everyone simply took their own share from the

collective experience and moved on.

As a curator, I considered working

in Europe or Türkiye, pursuing a PhD, or switching fields.

While researching, I discovered the

University of Alberta and Natalie Loveless.

It was exactly what I was looking

for—a university and supervisor where I could pursue a PhD freely, without

preconceptions or judgment.

I applied and was accepted.

Before the pandemic ended, during a

brief window when international travel was allowed, I flew to Edmonton via

Seoul wearing an N95 mask.

And I met Natalie Loveless in

person.

She became my supervisor.

I was incredibly lucky.

In Australia, my two beloved

cats—Sylvia, whom I adopted, and Gordon, who was born with an anomaly and

survived thanks to major surgeries—were cared for by dear friends in Canberra

for a month. Then they were sent to me in Edmonton via pet cargo.

A new continent, a new country, a

new university began.The first two years were very difficult. Building a life

in a country I didn’t know, where I knew no one—finding a home, settling in

with my cats, learning the system, keeping up with medical care for myself and

my cats—none of it was easy. The pandemic was still ongoing, albeit more

mildly.

International travel kept opening

and closing, so my family couldn’t come, and I couldn’t go.

We all know that the world doesn’t

treat migrants—or those forced to migrate—with sensitivity, kindness, or

tolerance. Instead, it often treats them with condescension and contempt.

Knowing that is one thing; living it

is another. Migration is truly hard.

Of course, my mother and my

father—who I saved in my phone as “strategy”—supported me. I always felt the

spiritual support and closeness of my relatives and friends back in Türkiye.

After two years, my mother came, and

we spent that summer together in Canada.

We filled my fridge with

Mediterranean olive oil dishes, sewed lace curtains together, and explored. Both

my parents wanted me to be happy—though they spoke different languages when

expressing it.

I managed to merge those two

languages.

I often saw myself as a

bridge—connecting different perspectives, traditions, and cultures.

Being born and raised in Istanbul, a

bridge between Asia and Europe, and receiving a Western, Anglo-Saxon education

in top schools while also knowing Eastern spirituality, values, and communal

traditions, naturally made me feel like a bridge.

Living in different countries and

continents, visiting museums, exhibitions, and ancient sites around the world

helped me understand humanity’s shared values and the intersections of

cultures. So, not just through reading and research, but through seeing,

feeling, and experiencing, I gained insights that opened up the field of art,

science, and social justice for me.

Experiencing Stendhal syndrome with

my mother in front of a tapestry at the Vatican Museums; Waiting in line at the

British Museum; Leaving the Hiroshima Museum feeling as if the nuclear bomb had

scorched every cell in my body.

Watching my grandmother touch a

Roman-era fertility goddess statue at the Istanbul Archaeology Museum and then

touch us, saying “May you be blessed” in true Eastern fashion (Western

tourists thought this was a ritual and everyone touched the statue and then

each other). These were some of my

adventures, and I’m glad they happened.

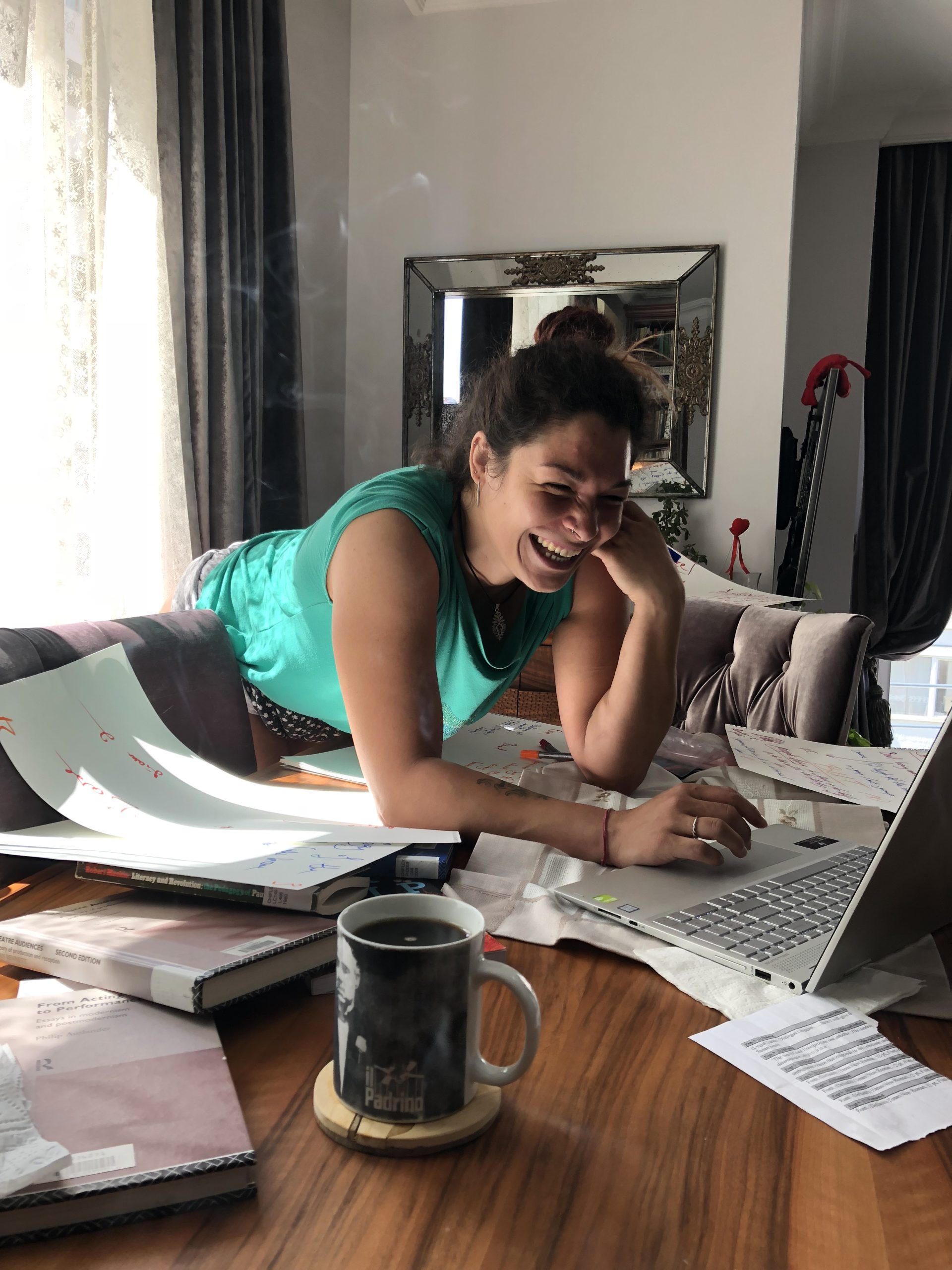

My last two years at the University

of Alberta—with my supervisor Natalie Loveless, my professors, colleagues, and

wonderful students, and that massive library—were beautiful and joyful.

Embracing my students, watching them

grow, and pushing myself to learn more so I could guide them better was deeply

fulfilling.

Learning, contributing to the spread

of knowledge and vision, expanding perspectives—these were no longer goals: they

were life itself.

And my life was beautiful. I lived

fully, intensely, and deeply.

I had something to say.

I had a unique perspective to share

through my research.

My doctoral dissertation is titled

Everything is Permitted: Invitations to

Transgress in Contemporary Performance Art.

On January 18, 2025, I passed my

doctoral qualifying exam and became a PhD candidate. After that, presenting my

ideas and analyses at various panels and conferences, discussing my hypotheses,

was incredibly rewarding.

In the spring of 2025, I co-taught a

course (Themes in Contemporary Art) with my supervisor, and performed so well

that I was en route to teach my very own courses at MacEwan University that

following fall.

I couldn’t make it.

We no longer live in Newton’s era,

nor Einstein’s. We now realize that the cosmos we perceive through our five

senses is not limited to human perception.

Despite advances in physics, and

despite centuries passing since Hammurabi’s laws and the Magna Carta, despite

knowing that “everything is connecting” means more than a phone commercial, our

steps toward social justice remain tiny.

If my life and efforts can be a

single drop of water for social justice on this planet, then I am grateful.

My final words, as I wrote at the

beginning of my master’s thesis:

‘’Thank you to everyone who

contributed to my life.’’

Yüksel Yılmaz (Mom), on behalf of the incomparable and forever loved Elif Su Yılmaz.

Elif Su Yilmaz is interested in untangling the methodical

construction of binary fallacies in the narratives that describe and/or are

attributed to marginalized groups, as it is materialized in artistic form.

Taking a transnationalist and transdisciplinary approach that stems from her

personal experiences as an immigrant as well as her academic background in the

fields of psychology and philosophy, Elif Su seeks to address how and why,

apart from the economic mandates of late capitalist system, certain false

consciousnesses are constructed and disseminated by various media apparatus in

service of maintaining the status quo.

Focusing primarily on contemporary performance art and art

theory, her research aims to contribute to the empowerment of historically and

contemporarily silenced voices in the collective effort to redress and

reconcile past and present injustices

I never met Elif Su, which is my loss. I

salute her for the progressive, humanist, activist she was as an individual. I

congratulate wholeheartedly, her academic success as a graduate of multiple

disciplines, and today awarded PhD in “History of Art, Design and Visual

Culture” by the University of Alberta. Most

of all, I thank her, and I honor the “modern” young Turkish woman who

represented her country successfully, carrying Ataturk’s vision for modern

Turkey to the world. She made Turks living in Canada proud.

CHOSEN

Incomparable Elif Su

Of all why you?

Rumi says, “There is no separation

If you love with your heart and soul.”

Mortals love with their eyes.

Unable to realize

Your divine chosen role.

Always determined and strong

Yet, fragile and sweet like a love song.

Lived life fully, accomplished more than many

So long…..and well-done baby!

Incomparable Elif Su

Chosen, you.

Dilara Yegani, President of Canadian

Young Turks Foundation

November 19, 2025, Edmonton Canada